- Share on Facebook116

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Twitter

The world’s most dangerous animal might have just met its match — modern science. The animal in question kills more people than any other, but it isn’t the alligator or shark; think smaller, with more legs.

That’s right, it’s the mosquito, an animal that kills more people each year than most wars and disasters. However, that could one day change, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently paving the way for an initiative that could dramatically reduce — and even perhaps one day eradicate — the mosquito.

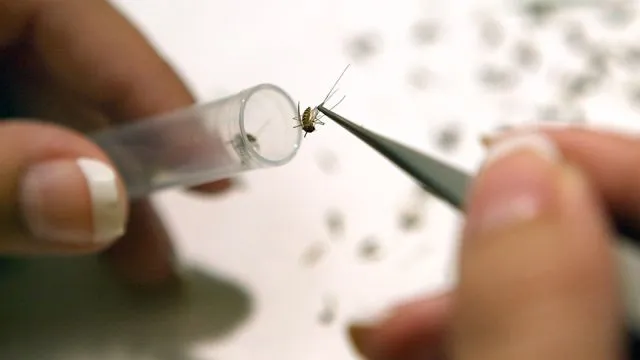

On Monday, the Kentucky-based biotechnology company MosquitoMate announced the EPA had greenlighted the release of male mosquitoes infected with a bacteria that stops breeding.

These lab-grown mosquitoes, dubbed ZAP males, are infected with Wolbachia bacteria. When the ZAP males mate with a female, her eggs become unable to hatch, thus cutting off the mosquito life cycle.

Wolbachia is commonly found in other insects such as fruit flies, though it doesn’t usually naturally infect mosquitoes outside the lab. However, the bacteria doesn’t just impede reproduction. Back in 2008, researchers from the University of Queensland in Australia found Wolbachia had the unexpected side effect of making some fruit flies less susceptible to viruses. This is believed to happen to mosquitoes as well. In other words, Wolbachia has a two-pronged strategy for making it harder for mosquitoes to give you a nasty disease. First, it makes the mosquitoes themselves more resistant to disease. Then, it makes it harder for mosquitoes to breed in the first place.

None of this is new, and for years health officials the world over have been eyeing Wolbachia as a possible way to tackle the global problem of mosquito-borne diseases. What’s changed is that now, that possibility could be about to be put to the test on a large scale.

According to MosquitoMate, the EPA has approved the sale and use of their lab-grown ZAP males in 20 states. The company has a five-year license and says it could start distribution by next summer. According to Quartz, two early areas being considered include Nashville, Tennessee and Lexington, Kentucky. While the company so far is reportedly focusing on securing government contracts, it’s also marketing its product to the general public.

“MosquitoMate starts releasing male ZAP mosquitoes weekly in your yard at the beginning of the mosquito season,” the company says on its website. “The resulting eggs do not hatch, decreasing your biting mosquito population,” they explained.

They added, “Our technology only impacts mosquitoes and does not harm or affect other insects, including bees and butterflies. It’s that simple.”

The company boasts that its method is not only safe for other insects, but also for humans, too. They pointed out their use of bacteria-infected males means fewer chemicals and no use of genetic modification.

Complete eradication of mosquitoes?

For now, MosquitoMate is promoting their method as a way to reduce pesky mosquito populations, though some health experts say we should eventually go further — much further. “We should consider the ultimate swatting,” Biologist Olivia Judson once told The New York Times.

As far back as 2003, she was advocating for the complete eradication of 30 species of mosquito known to carry dangerous diseases. She argued such an effort would barely reduce the genetic diversity of the mosquito family by 1 percent, while saving potentially millions of human lives.

To give you an idea of how many lives we’re talking about: according to the World Health Organization, the mosquito kills an estimated one million people each year and is easily nature’s biggest killer. To put in perspective, sharks kill an average of six people each year globally, according to the monitoring group ISAF. Meanwhile, the Syrian civil war has killed around 465,000 over six years, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights.

Another way to think about it is to consider that barely one million people died during the entirety of the American Civil War. If we extrapolate based on the WHO’s current data, since the civil war ended in 1865, globally mosquitoes may have quietly killed more than 150 million people, nearly half the current U.S. population. No matter how you cut it, mosquitoes are killing us on a massive scale, mostly through the spread of malaria and other infectious diseases like dengue and West Nile virus.

Will there be side effects?

However, not everyone thinks a mosquito massacre is such a good idea. According to Florida University entomologist Phil Lounibos, eradication is “is fraught with undesirable side effects.”

Speaking to the BBC, he explained that mosquitoes can contribute to the environment in surprising ways, such as by pollinating plants when they feed on nectar. They’re also a critical source of food for everything from frogs to fish, birds to bats. So killing off mosquitoes could impact other animals higher up the food chain — or worse.

Lounibos warned that if mosquitoes suddenly disappear, the hole they leave in the eco-system could be filled by any number of other nasty bugs. Therefore, by killing off mosquitoes, we could be merely replacing the devil we know with something that might be far worse.

Then there’s the potential environmental impact. Speaking to NPR, science writer David Quammen has argued mosquitoes may have inadvertently slowed climate change by making “tropical rainforests, for humans, virtually uninhabitable.”

“Nothing has done more to delay this catastrophe over the past 10,000 years, than the mosquito,” he suggested, hinting that many of the world’s rainforests might not be in such a pristine state if it wasn’t for mosquitoes warding off human settlement.

Either way, sooner or later we’ll have to decide whether or not it’s time for the mosquito to go the way of the dinosaur. Although MosquitoMate remains focused on local and regional mosquito management, other companies internationally have already gone further in experimental trials.

During one trial carried out by British biotech firm Oxitec in 2009-10, the use of genetically modified males managed to kill off 96 percent of the mosquito population in one area, when compared to surrounding regions. This shows a mosquito genocide is quickly becoming an achievable goal; the only question is whether or not we should actually do it.

— Ryan Mallett-Outtrim

- Share on Facebook116

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Twitter