- Share on Facebook115

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Twitter

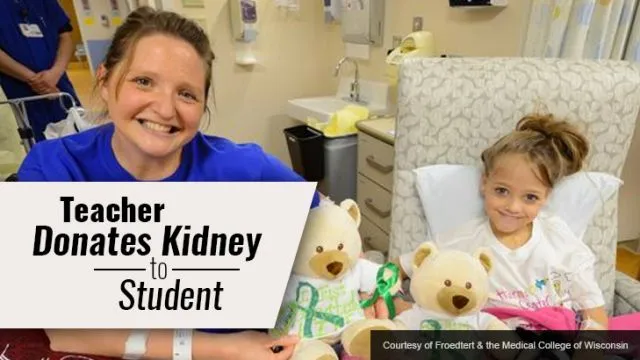

An eight-year-old first grader was in desperate need of a kidney transplant had a teacher come to the rescue. The operation took place on May 24 at Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin for the youngster and at Froedtert Hospital for the teacher — just a block from each other in Milwaukee.

Jodi Schmidt, a third-grade teacher at Oakfield Elementary School in Oakfield, Wisconsin, decided to donate her kidney to Natasha Fuller, a little girl desperately in need of a transplant. The little girl stayed alive only thanks to thrice-weekly kidney dialysis, but this treatment wasn’t going to be an option much longer.

Prune belly syndrome

Natasha was born with a rare birth disorder known as prune belly syndrome, in which the stomach muscles are partly or totally absent and the urinary tract is malformed. Also known as Eagle-Barrett Syndrome, chronic kidney failure often results from the urinary tract malformation. It’s likely that throughout her life, Natasha’s bladder was enlarged. She’s an exception in that prune belly syndrome overwhelmingly affects males, who also suffer from undescended testicles.

Prune belly syndrome varies in severity. Sometimes minor bladder surgery is required, and in males an operation can pull the testes into the scrotum. A kidney transplant for prune belly syndrome is rare. Natasha had been on the waiting list for a kidney transplant for some time, but recurrent infections — a common occurrence in prune belly syndrome — took her off the transplant list until recovery.

The gift box

Natasha lives with her grandparents, Chris and Mark Burleson, so that she can receive the treatment she needs at Children’s Hospital. Her parents and twin sister reside in Oklahoma. Schmidt gave Natasha’s grandmother a carefully wrapped gift box, which contained a note stating that Schmidt was a match for Natasha and that she would donate a kidney.

The decision

Schmidt is married and the mother of three. She knew of Natasha’s condition and often saw the young girl in the hallway at school. Natasha would always wave and smile. Although she knew Natasha was severely ill and in pain, it wasn’t obvious in her attitude. Natasha remained upbeat and outgoing.

After praying, Schmidt felt called to help Natasha and underwent testing to see if there was a match. In addition, Schmidt and her husband Rich and their friends raised money to pay for some of Natasha’s medical expenses and travel expenses for her family.

Kidney transplant

A transplanted kidney can come from either a living donor or a cadaver. Generally, all of the costs associated with a living donor’s kidney are paid for by the recipient’s insurer. Living donor donations usually produce better results for the recipient; there are lower risks of rejection and start functioning more easily than a cadaver kidney. There’s also the fact hospitals can schedule such surgeries, while a cadaver donation occurs on an emergency basis from a recently deceased person.

Schmidt’s remaining kidney is sufficient to take over the lost kidney’s function, and will enlarge in order to do so. She can eat and generally live life normally with one kidney, and shouldn’t require any special medication. Women who have donated kidneys can get pregnant and give birth.

Kidney donor prohibitions

Most healthy people can serve as kidney donors. However, people diagnosed with certain diseases or conditions cannot safely donate a kidney. Besides those suffering from kidney issues, these include the following:

- High blood pressure

- Obesity

- HIV infection

- Serious psychiatric illness

- Bleeding disorders

- History of embolism or thrombosis

- History of melanoma or any metastatic cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic lung disease

Swim and eat chocolate and fries

When asked what she wanted to do now that she has a new kidney, Natasha replied she wanted to go swimming and eat chocolate and fries. Maybe the latter two wishes aren’t the healthiest treats, but who can blame a little girl for whom they’ve always been forbidden?

When the pair saw each other for the first time post-surgery on May 27, they agreed they were now “kidney twins for life,” and looked forward to seeing each other at the start of the school year in September.

—Jane Meggitt

- Share on Facebook115

- Share on Pinterest

- Share on Twitter