Twenty years ago, American Star Trek fans gasped in awe and fascinated fear as the Borg announced, “You will be assimilated.” They were humanoid, but they weren’t quite human. Flesh and bone had been intertwined with metal and electronics, crafted together to create something both human and machine.

Fast forward and we’ve decided to tackle the same conundrum of life in an entirely different way. We’re now building things that have traditionally been built with metal and wires – robots – with organic materials.

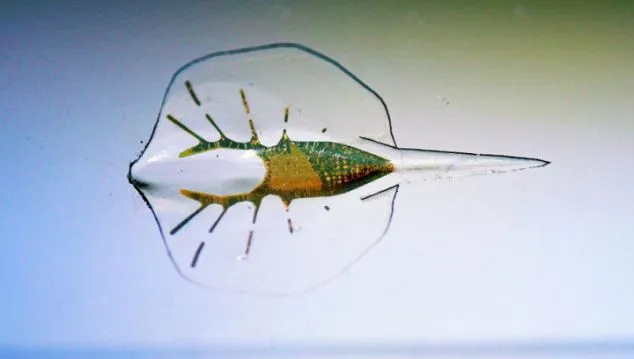

Introducing the cyborg stingray. It is the first of its kind. It swims. It responds to light signals. It is powered by a rat’s heart.

You heard that correctly.

Muscles taken from the heart of a rat make up the cyborg’s base. The muscles are intricately woven into a golden spine and surrounded by a thin layer of rubber. The skeleton design is based on that of the batoid fish. The muscles have been genetically altered to respond to light, creating movement that allows the bio-robot to travel gracefully through water. Just like a real stingray.

Newsy’s made a great video comparing the two:

Dr. Kit Parker, a bioengineer at Harvard University, is the mastermind behind this technology. He had previously engineered a jellyfish. His aim is to create more than robotic, flesh-driven creatures. In fact, Parker told NPR that designing the stingray was little more than a training exercise. The ultimate prize is a human heart.

Like all tech masterminds, Parker and his team are building off the grand pool of human research and intellect that eventually moves our science forward. Dr. Rashid Bashir of the University of Illinois was the first to meld a franken-creature from the muscles of a rodent. These first prototypes were controlled by electrical pulses, but researchers had little control. Soon after that, Bashir’s team developed critters whose beating muscles allowed them to walk. Researchers could control their speed by adjusting the frequency of the electric pulse that elicited this muscular response.

Parker’s team can dictate the speed of their swimming stingray by adjusting the light’s frequency. They can also manipulate the bot’s movement so that only the left or right fin moves, for the first time allowing directional control. The tiny device can easily be guided through an obstacle course. In fact, it has been. There’s a video.

Bashir has his own vision for this emerging technology. His Golden Fleece isn’t the human heart, it’s creating tiny biological machines that can better deliver lifesaving medication. “Such devices would allow patients’ own bodies to become part of the solution,” he promises. He doesn’t stop there. “We’re also interested in building living machines that can do things like sense toxins in water and potentially neutralize them.”

Dr. Parker’s team promises that the next critter will be even more complex, though he won’t say what exactly. Much like the human health uses of this technology, the possibilities are endless.

–Erin Wildermuth